Salk researchers discover how liver responds so quickly to food

The finding could help better understand metabolism and some forms of diabetes

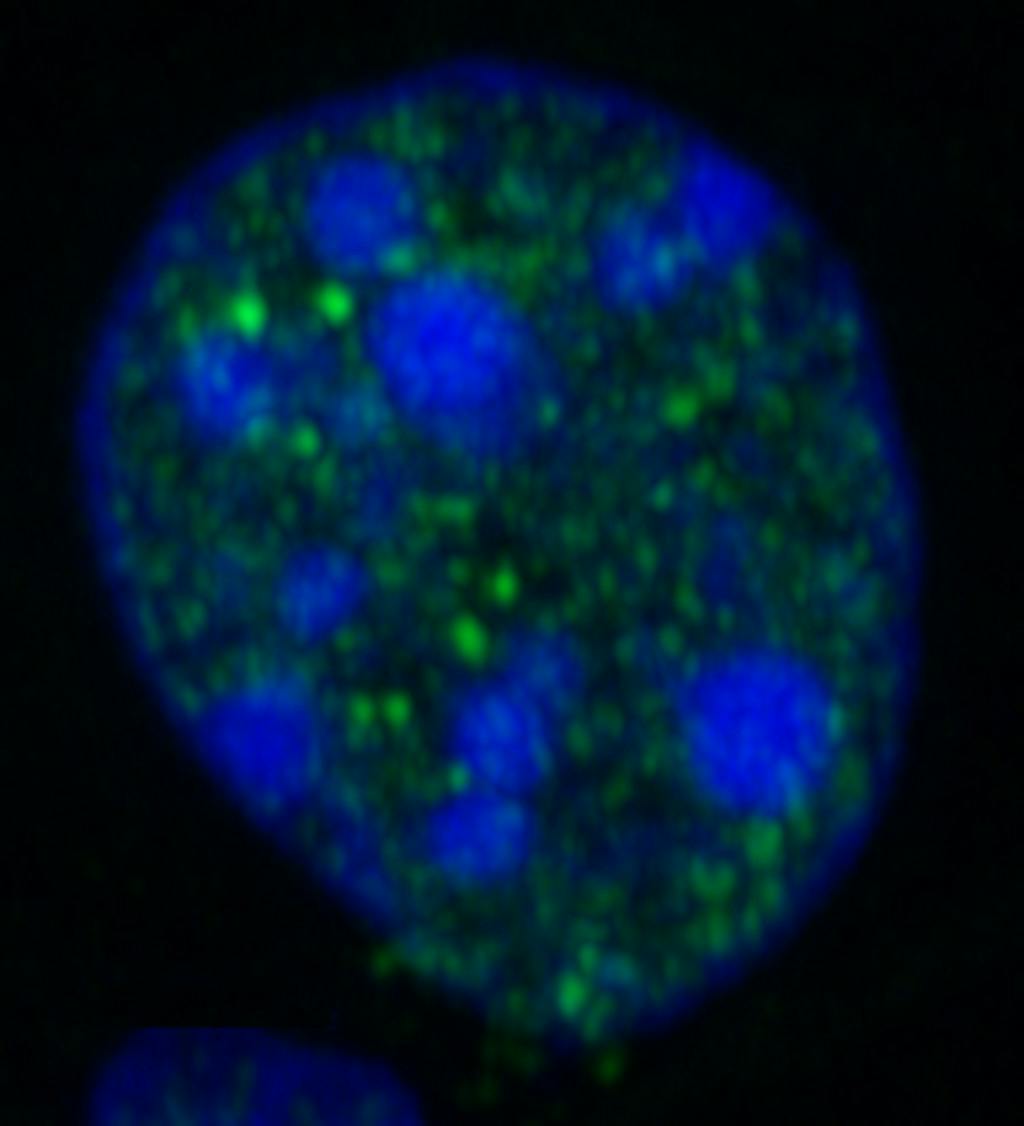

Image shows NONO protein immunostained green in liver cells after a meal. Blue indicates cell nuclei.

LA JOLLA—Minutes after you eat a meal, as nutrients rush into your bloodstream, your body makes massive shifts in how it breaks down and stores fats and sugars. Within half an hour, your liver has made a complete switch, going from burning fat for energy to storing as much glucose, or sugar, as possible. But the speed at which this happens has flummoxed scientists—it’s too short a time span for the liver’s cells to activate genes and produce the RNA blueprints needed to assemble new proteins to guide metabolism.

Now, Salk researchers have uncovered how the liver can have such a speedy response to food; liver cells store up pre-RNA molecules involved in glucose and fat metabolism.

“The switch from fasting to feeding is a very quick switch and our physiology has to adapt to it in the right time frame,” says Satchidananda Panda, a professor in the Salk Institute’s Regulatory Biology Laboratory and lead author of the paper, published February 6, 2018 in Cell Metabolism. “Now we know how our body quickly handles that extra rush of sugar.”

It was known that a RNA-binding protein called NONO was implicated in regulating daily (“circadian”) rhythms in the body. But Panda, along with first author Giorgia Benegiamo, a former graduate student in the Panda lab, and their collaborators wondered whether NONO had a specific role in the liver. They analyzed levels of NONO in response to feeding and fasting in mice. After the animals ate, speckled clumps of NONO suddenly appeared in their liver cells, newly attached to RNA molecules. Within half an hour, the levels of corresponding proteins—those encoded by the NONO-bound RNA—increased.

“After mice eat, it looks as if NONO brings all these RNAs together and processes them so they can be used to make proteins,” says Panda.

When mice lacked NONO, it took more than three hours for levels of the same proteins, involved in processing glucose, to increase. During that time lag, blood glucose levels shot up to unhealthy levels.

Since blood glucose levels are also heightened in diabetes, the researchers think that the mice without NONO may act as a model to study some forms of the disease.

“Understanding how glucose storage and fat burning are regulated at the molecular level will be important for the development of new therapies against obesity and diabetes,” says Benegiamo.

Questions still remain about how exactly NONO is triggered to attach to the pre-RNA molecules after a meal. And Panda is hoping to assemble a more complete list of all the pre-RNAs that NONO binds to—in both the liver and other parts of the body. NONO has been found at high levels in the brain and muscle cells, so the researchers are planning studies to see whether is reacts similarly in those organs to food.

Other researchers on the study were Ludovic Mure, Galina Erikson and Hiep Le of the Salk Institute and Ermanno Moriggi and Steven Brown of the University of Zurich.

The work and the researchers involved were supported by the Salk Institute, the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Helmsley Foundation, the American Federation for Aging Research, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Neurological Diseases and Stroke, the Waitt Foundation, the Chapman Foundation, the Society for Neuroscience, and the Hartmann-Mueller Foundation.